The Abilene Paradox in Online Communities: Why Your Members Agree to Things Nobody Wants (And How to Fix It)

Scenario: your online community team schedules a highly anticipated virtual event for 3 PM EST. West Coast members are still deep in their workday. European members have already logged off. East Coast parents are handling school pickup. But nobody speaks up during planning because each assumes everyone else is fine with it.

Launch day arrives. Attendance is half what you expected. Post-event surveys reveal widespread frustration about the timing—yet not a single person raised concerns beforehand. Everyone assumed the decision was already made.

This situation is an example of the Abilene Paradox. And if you've never heard of it, you're not alone—even though it's been hiding in plain sight in your community for years. Although I have spent many years in the online community practice as a strategist, it amazed me that I have only just recently encountered anyone putting a name to a situation I have long recognized.

Naming something can give you power over it. Awareness of a thing means that you can plan how to control it. So let’s take a closer look at this idea, how it plays out in online communities, and what you can do as a community professional to prevent it from happening.

What Is the Abilene Paradox?

The Abilene Paradox occurs when a group collectively agrees to a decision that contradicts the preferences of most (or all) members. It happens when individuals stay silent about their objections, mistakenly believing others support the choice. The result? A community proceeds with an action that essentially no one wanted, leading to frustration, disengagement, and poor outcomes.

Management expert Jerry B. Harvey coined the term in 1974 after a personal experience: on a sweltering Texas afternoon, his family agreed to drive 53 miles to Abilene for dinner. The trip was hot, uncomfortable, and no one enjoyed it. Afterward, they discovered that none of them had actually wanted to go—each had agreed only because they thought the others were enthusiastic.

Harvey named this phenomenon after that destination, and it's been studied ever since as a classic example of mismanaged agreement.

Why Online Community Managers Need to Know This

If you've been working in community management since the early days of digital forums, social intranets, or private networks, you might wonder how you've never encountered this concept before. You're not alone.

The Abilene Paradox originates from organizational behavior and management literature—not community management curricula. Most community training focuses on engagement tactics, moderation, and conflict resolution, rarely touching formal group decision-making theory. And yet, the dynamics of the paradox are especially pronounced in online contexts, where silence is easy to misread as agreement.

Here's why it matters to you:

Silent agreement is the default online. In face-to-face settings, body language and tone can signal hesitation. Online, a lack of response often looks like consensus. This makes digital communities uniquely vulnerable to the paradox.

Poor decisions erode trust fast. When members realize they collectively agreed to something no one wanted, it breeds cynicism and disengagement. They stop believing their voices matter.

You can't afford collective missteps. Whether you're managing a customer community, a nonprofit advocacy network, or an internal digital workplace, decisions that miss the mark waste time, money, and goodwill.

Understanding and addressing the Abilene Paradox is foundational to building communities where members feel heard, valued, and genuinely aligned with decisions. Part of building that space entails meeting the baseline conditions for open dialogue in your online community, which I address in my article about building safe spaces online.

How It's Different from Groupthink and Pluralistic Ignorance

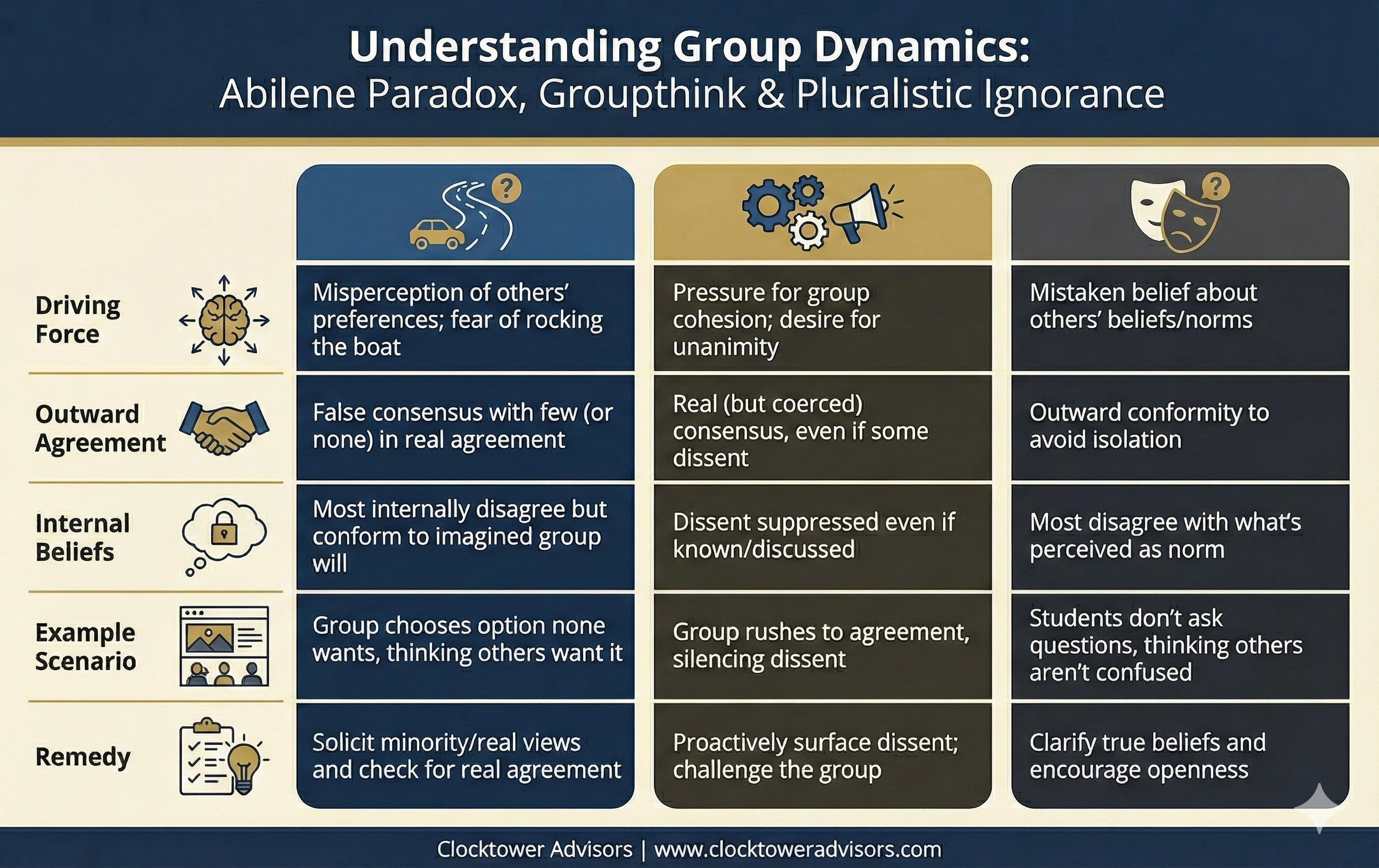

You've probably heard of groupthink or (maybe) pluralistic ignorance. The Abilene Paradox shares DNA with both but operates differently. Here's how to tell them apart:

The Key Distinctions:

Abilene Paradox: No one wants the outcome, but everyone thinks others do.

Groupthink: Everyone expresses agreement to maintain harmony, suppressing known dissent.

Pluralistic Ignorance: People conform because they think others accept a norm, when most actually don't.

The distinction matters because the solution to each is slightly different. For the Abilene Paradox, the fix is to surface real preferences actively.

Real-World Examples from Online Communities

Let's make this concrete. Here are scenarios that may sound familiar:

Example 1: The Silent Meeting Time Trap

A community manager schedules a virtual town hall at 3 PM EST, thinking it works for most members. In reality, West Coast members find it too early (interrupting their workday), European members can't attend (it's evening), and East Coast parents struggle (school pickup time).

But nobody speaks up because each assumes others are fine with it. The event proceeds with low attendance. Post-event surveys reveal widespread dissatisfaction—yet no one raised concerns beforehand.

Example 2: The Over-Gamified Community

A B2B SaaS community introduces an elaborate point system, badges, and leaderboards to "boost engagement." Managers assume members love it because no one complains publicly.

In reality, most members find it trivializing. They feel the competitive elements undermine the collaborative, professional tone they valued. They don't object because they assume others enjoy the gamification. Over time, high-value contributors quietly leave, and discussions become shallow.

Example 3: The Policy No One Wanted

A nonprofit community's team proposes requiring all testimonials from members to be pre-approved by moderators (to ensure message consistency). A few vocal contributors express support, wanting to avoid off-brand messaging.

The majority of active members fear this will stifle grassroots energy and authentic voices, but they don't speak up, assuming leadership has already made the decision. The policy is implemented. Participation in advocacy campaigns drops sharply.

Example 4: The Event That Missed the Mark

A community plans a virtual happy hour to "build connections," assuming that everyone wants casual socializing. In reality, most members joined for professional development and practical help—they're busy and see social events as low-value.

No one voices this concern (fearing they'll seem antisocial), so the event proceeds with minimal attendance and awkward silence for those who did show up. Members leave wondering why they're not "community people."

Sound familiar? You're witnessing the Abilene Paradox in action.

Six Practical Tools to Prevent the Abilene Paradox

Here are a few ways that you can combat this dynamic with deliberate, actionable tactics:

Tool 1: The Devil's Advocate Role

What it is: Designate one member (rotating monthly) to explicitly challenge proposals during decision discussions.

How to implement:

Announce the role publicly: "This month, [Name] will ask tough questions about any major decisions to ensure we've thought things through."

Give them a script: "I'm playing devil's advocate—what are the downsides of this approach?"

Rotate the role so no one is typecast as "the negative person."

Why it works: It legitimizes dissent and removes social stigma from questioning group decisions. When disagreement is built into the process, members feel safer voicing concerns.

Tool 2: Anonymous Feedback Channels

What it is: Create a private, anonymous survey or suggestion box for members to voice concerns without social penalty.

How to implement:

Use tools like Google Forms, Typeform, or built-in community polling features.

Ask: "Do you support this decision? If not, what concerns you?"

Share anonymized results publicly: "We heard concerns about X—let's discuss."

Why it works: Removes fear of judgment and surfaces hidden objections. Members who would never speak up publicly will often share candidly when anonymous.

Tool 3: Actively Solicit Dissent

What it is: Actively invite objections during decision-making, both publicly and privately.

How to implement:

In announcement posts, add: "We want to hear concerns—what could go wrong with this plan?"

Send private DMs to quieter, thoughtful members: "You haven't weighed in yet—do you have reservations?"

Use "silent brainstorming" techniques where everyone submits concerns privately before group discussion.

Why it works: Signals that disagreement is valued, not punished. It reframes silence as something to question, not accept.

Tool 4: Pre-Decision Check-Ins

What it is: Before finalizing decisions, pause and explicitly ask: "Does anyone disagree but hasn't spoken up?"

How to implement:

In meetings or threads, say: "I'm sensing consensus, but let's make sure—does anyone have concerns they haven't shared?"

Use a "fist-to-five" voting system: everyone rates support from 0 (opposed) to 5 (enthusiastic). Anything below 3 triggers discussion.

Why it works: Creates a checkpoint to surface silent objections before it's too late. It acknowledges that silence doesn't equal agreement.

Tool 5: Post-Decision Debriefs

What it is: After implementing decisions, revisit them openly to uncover hidden dissent and learn.

How to implement:

30-60 days post-decision, post: "How's [decision] working? Did anyone have concerns they didn't voice initially?"

Frame it as learning, not blame: "We want to improve our process—what did we miss?"

Why it works: Builds trust that leaders care about real input and improves future decision-making. It also gives members permission to speak up next time.

Tool 6: Build Psychological Safety Through Modeling

What it is: Community leaders and managers model vulnerability by admitting uncertainty and inviting correction.

How to implement:

Leaders say: "I'm not sure this is the right call—talk me out of it."

Managers publicly thank members who disagree: "Great point—I hadn't considered that."

Celebrate "productive conflict" stories in community highlights.

Why it works: Demonstrates that dissent is safe and valued, encouraging others to speak up. When leaders show they don't have all the answers, members feel empowered to contribute theirs.

How to Implement These Strategies in Your Community

Knowing the tools is one thing. Putting them into practice is another. Here's how to integrate these tactics into your community governance and decision-making processes:

Start small. Pick one or two tools and pilot them in lower-stakes decisions first. Test anonymous feedback on a proposed event schedule before using it for platform migrations.

Communicate the "why." Explain to your community that you're trying to ensure decisions truly reflect member preferences, not just vocal minorities or silent assumptions.

Educate your community. Share this article or a summary of the Abilene Paradox with your members. Simply teaching people about the phenomenon can help them recognize and resist it.

Make it part of your culture. Build these practices into your community charter or governance documents. Normalize dissent as a contribution, not a problem.

Train your moderators and leaders. Ensure they understand how to invite and handle dissent productively. Role-play scenarios where they practice soliciting minority opinions.

Measure and iterate. Track whether decisions made with these tools lead to better engagement and fewer post-decision complaints. Adjust your approach based on what works.

These principles, which exemplify iteration, transparency, coaching and measurement, will be familiar to community professionals who have spent any time in the trenches. The intentional inclusion of dissent as part of the community culture, however, may be something new and will require education, experimentation, and evolution to discover what fits best with the community you manage.

In my own practice, I have found that there is no single approach that can be universally applied to welcoming dissent. Like all social systems, it is highly variable. What’s more, the preferences will probably shift over time as new members join the community and longtime members fade.

Take the Next Step

The Abilene Paradox thrives on assumptions—that silence means agreement, that others are on board, that speaking up is risky. As a community manager, your job is to dismantle those assumptions and create a culture where real preferences, not imagined consensus, drive decisions.

Your members want to be heard. They want to believe their input matters. But they need you to create the conditions where speaking up feels safe, valued, and expected.

So the next time you're about to finalize a major decision, pause. Ask yourself: Do I actually know what my members want, or am I assuming? Then use one of the tools above to find out.

Is your community silently agreeing to the wrong decisions?

Let's talk. Book a free 30-minute Community Strategy Session and I'll help you diagnose what's working—and what's not.

Key Takeaways

The Abilene Paradox occurs when groups agree to decisions no one wants because everyone assumes others support it.

It's especially common in online communities, where silence is easy to misread as agreement.

It's distinct from groupthink (coerced consensus) and pluralistic ignorance (misreading norms).

Combat it by actively soliciting dissent, using anonymous feedback, appointing devil's advocates, and building psychological safety.

Make these practices part of your community culture and governance, not one-off experiments.